Cutting ties: Student group urges SU to end relationship with Adidas, seeks to promote fair labor practices

More than a decade after a student group organized a naked bicycle ride through campus to protest Syracuse University’s ties with sweatshops, the movement for fair labor practices has made its way back to campus.

Jose Godinez, an undeclared freshman in the Martin J. Whitman School of Management, re-introduced the United Students Against Sweatshops organization to campus in February after a motivating lecture from visiting Haitian and Honduran sweatshop workers. The group hopes to eliminate SU apparel made in poor working conditions, he said.

On Wednesday, the group plans to hold a walk commemorating the 12th anniversary of SU joining the Workers Rights Consortium, an organization that holds corporations accountable and supports workers’ rights by enforcing codes of conduct. As part of the walk, every member will go to the chancellor’s office and drop off a letter explaining what actions they would like to see from the university. This will be followed by a demonstration during which group members will cut an Adidas tie, symbolizing their desire to see SU cut its ties with Adidas.

Godinez said he believes the anti-sweatshop movement on campus died down in the last decade as student protests shifted their focuses toward issues such as the war in the Middle East and the economy, he said. But he said he believes the momentum is right to restart the student organization and help SU put a stop to the many factories with poor working conditions.

One of the reasons is the “Badidas” campaign, which has come to SU, he said. “Badidas” is a movement that encourages universities to drop Adidas as a sponsor because of the company’s refusal to pay $1.8 million to 2,800 sweatshop workers in Indonesia, according to the “Badidas” campaign website.

“SU does a great job monitoring sweatshops and their collegiate apparel supply chain. I think the best thing for SU to do is cut their contract with Adidas,” he said. “The sweatshop battle isn’t going to be won overnight. It’ll be a step-by-step process. We’ll keep going after the factories that are violating the (Worker Rights Consortium) and SU’s policies.”

SU has made efforts to eliminate unfair working conditions among manufacturers that are licensed to produce SU apparel. While considered one of the most active schools in advocating against sweatshops, the university continues to license companies that are known to have poor sweatshop conditions.

The merchandise available at SU currently comes from 3,113 factories in 46 countries, according to the consortium’s website. The university does not condone the use of sweatshops to produce apparel, said Jamie Cyr, associate director of SU’s auxiliary services, in an email.

“We don’t just want to make a point, we want to make a very definite difference in people’s lives by endorsing a product that can be enforced and that will not result in unintended, negative repercussions for those we are trying to protect,” Cyr said.

After joining the Worker Rights Consortium in March 2001, SU agreed to observe the consortium’s labor codes. These codes include a guaranteed living wage for workers and their families, standards on working hours, a safe and healthy working environment, and protection from harassment and abuse, according to the consortium’s model code of conduct.

The school continued to license the same companies after its affiliation with the consortium, but began holding factories to higher standards, said Betsy English, director of the University Bookstore, in an email.

The bookstore staff assesses new companies in the collegiate market and determines whether their working conditions meet the bookstore’s guidelines before licensing the company, she said.

Wednesday will mark SU’s 12th anniversary with the WRC. Because of the school’s successful athletic program, SU has become one of the consortium’s most important affiliations, said Scott Nova, executive director of the WRC.

“It’s significant because universities like SU with large licensing programs have clout in the apparel industry,” he said. “Companies like Nike and Adidas care about what SU thinks.”

Nova added that SU is one of the most active affiliated schools and is often involved in key cases with factory conditions. He considers them a strong partner of the consortium.

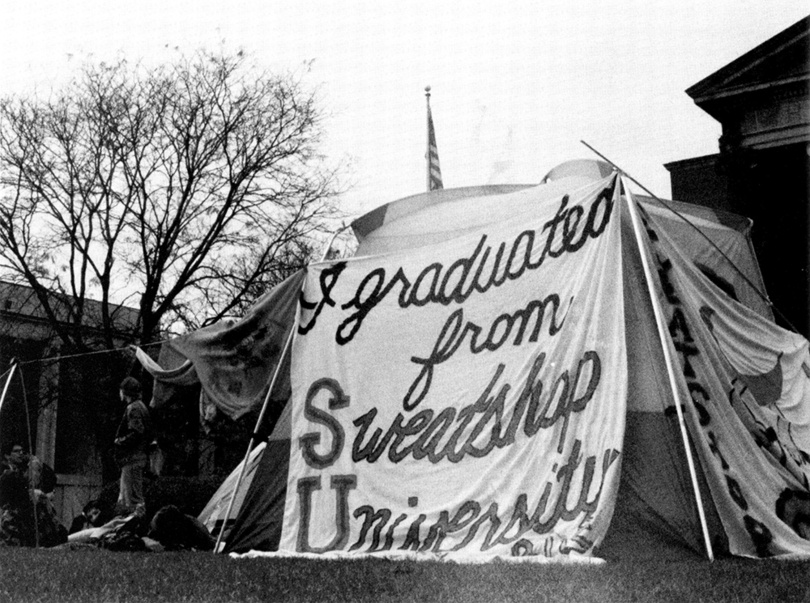

SU joined the WRC after pressure from both the Student Coalition on Organized Labor and the United Students Against Sweatshops between March 2000 and March 2001. Their methods included protest marches, a naked bicycle ride across campus and an entire week devoted to sweatshop awareness with activities like mock sweatshops, a Quad camp-out and various theater shows, according to Swarthmore College’s Global Nonviolent Action Database.

Kenneth “Buzz” Shaw, who was SU’s chancellor at the time, said he was reluctant to affiliate SU with the WRC, but eventually agreed to affiliate the university with the labor rights monitoring organization.

“The problem was that (the WRC) was an advocacy group. You can’t expect them to be neutral and analyze things in an objective fashion,” Shaw said. “It was my hope at the time that the government had a better position to make change.”

Shaw said he made the major shift after further examination of the WRC and finding little change from the government regarding collegiate apparel and sweatshops.

Despite the university’s membership in the WRC and its continued effort to guarantee labor rights, a small percentage of companies licensed to print the SU logo have been the subject of WRC investigations, according to reports on its website.

One of SU’s largest licensees, Nike, is responsible for several factories that have breached the WRC’s rules.

Nike manufacturer Star, S.A. was investigated by the WRC in Honduras from May to October of 2012, according to the Oct. 12, 2012, report by the WRC. The factory already had a history of violating WRC regulations, as shown in a 2008 investigation by the WRC documenting verbal and physical abuse, forced overtime, and restrictions on bathroom and drinking water access. Union leaders continue to be threatened by violence and death. The threats have intensified since Gildan acquired the factory, according to the report.

But WRC investigations have helped improve conditions within some sweatshops. Hong Seng, a Nike factory in Thailand that produces SU apparel, was investigated for threatening to fire three pregnant workers, according to a Jan. 23 WRC report. After the WRC’s investigation, the factory kept all three workers, began providing Thai language courses to its Burmese workers and provided pregnant workers with information on Thai labor laws and social security benefits, according to the report.

In Indonesia, the owner of Nike and Adidas manufacturer PT Kizone, also used by SU, fled the country without paying $3.3 million in legally mandated severance, leaving more than 2,800 workers without compensated pay, according to a report on the WRC’s website. While Nike has given $500,000 to the workers, another SU licensee, Adidas, refuses to take responsibility and has not given workers any type of monetary reparation, according to the report. This inaction by Adidas sparked the “Badidas” campaign by the United Students Against Sweatshops group.

As a member of the WRC, SU is informed whenever licensee sweatshops are shown to have poor working conditions, said Nova, the WRC executive director.

But with more than 3,000 factories across the world, it becomes extremely difficult to monitor every single report, Shaw said.

“You can’t put all the blame on the university,” he said. “There are thousands of factories making the products overseas. It’s impossible for anyone to police all that.”

Published on March 25, 2013 at 2:37 am

Contact Alfred: alng@syr.edu

@alfredwkng